Data Turkey: Institutional Quality

- Posted by Pelin Dilek

- Posted on September 22, 2014

- Data&Charts

- Comments Off on Data Turkey: Institutional Quality

Does Institutional Quality Support Further Income Increase in Turkey?

Institutions are often regarded as one of the ingredients of competitiveness and/or growth rate in economic development. The discussion on the role of institutions in ‘the origins of power, prosperity and poverty’ got popular attention through Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson’s book, ‘Why Nations Fail’. The main idea behind the book is that inclusive economic and political institutions promote growth and prosperity while extractive institutions typically lead to stagnation and poverty[1].

Given the importance of institutional quality within a country’s economic development, we had looked at governance indicators in DataTurkey section of LongViewTurkey before (http://longviewturkey.com/dataturkey-governance/). The main outcome out of those data was that Turkey improved in some of the pillars of institutional quality (control of corruption, effectiveness of government between 2002-2012; but there was no significant improvement in rule of law and regulatory quality.

There are some other sources, which bring together data on institutional quality; but they tend to concentrate on corruption:

- Transparency International Corruption Index, Turkey’s ranking improved from 60% quintile in 2003 to 30% in 2013.

- In World Bank’s ‘Ease of Doing Business Survey’, Turkey ranks 69th out of 189 countries as of 2014. Within the index, Turkey’s worst scores are in ‘resolving insolvency’ and ‘starting a business’ while its best scores are in ‘protecting investors’ and ‘enforcing contracts’.

- The Corruption Perceptions Index ranks countries/territories based on how corrupt a country’s public sector is perceived to be. According to this index, Turkey ranks 53rd out of 177.

- Global Corruption Barometer on the other hand, surveys the experiences of everyday people confronting corruption. According to Global Corruption Barometer 2013, 54% of the respondents believe that corruption increased over the past two years. Among the most corrupt institutions, respondents listed political parties (66%), legislature (55%) and media (54%).

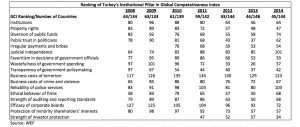

There is also one another source, which gives more comprehensive data on institutional quality. In World Economic Forum’s Global Competitiveness Index (released on September 3rd), there is institutional information on 21 sub-pillars collected from WEF executive opinion survey. As this is the only data that has been collected and released in 2014, we believe it is important in terms of the information it possesses. Below are some highlights from 2008-2014 data:

- Ranking in institutional pillar of Turkey’s competitiveness improved steadily until 2013, even though it always stayed below the ranking of the overall competitiveness index. In other words, institutional pillar always pulled down Turkey’s overall competitiveness.

- Between 2008-2013, Turkey improved in all of the sub-indicators of institutional pillar, except for judicial independence, business cost of terrorism and business cost of crime and violence. Of the three, ranking on judicial independence deteriorated continuously. These three are Turkey’s worst rankings in absolute terms as well.

- Between 2008-2013, Turkey’s ranking improved the most in ‘wastefulness of government spending’ and ‘transparency of government policy-making’.

- Yet, 2014 ranking results, point out to deterioration in most of the sub-indices of institution pillar compared to 2013. While the ranking in institutional pillar deteriorates to 64th position in 2014 from 56th in 2013, within the sub indices ranking of ‘public trust to politicians’ and ‘reliability to police services’ dropped the most.

- Turkey also loses competitiveness in 2014 due to ‘ethical behavior of firms’, ‘strength of auditing and reporting standards’ and ‘diversion of public funds’.

- Turkey’s institutional pillar strengthened via the rankings of ‘strength of investor protection’ and ‘efficacy of corporate boards’.

Comparative Data: What Happens in the EM World?

- Looking at our usual EM subset of 15 countries, we see that in all but three countries, ranking in institutional pillar is worse than the overall global competitiveness index. Countries, which have better institutional quality compared to GCI ranking are Chile, South Africa and India.

- The biggest (negative) disparity between institutional ranking and GCI ranking is in South Korea, Russia, and Bulgaria.

- Turkey’s strengths compared to other countries are in strength of investor protection and wastefulness in government spending.

- Its relative weaknesses are in judicial independence and business costs of terrorism.

- For illustration purposes, we plotted the ratio of institutional ranking to GCI ranking compared to GDP/capita. Excluding South Korea and India’s data (they have the max and min GDP data), we see that there is positive relationship between the two axis that we plot. In other words, higher the country’s relative ranking in institutions compared to its overall score, higher its GDP/capita.

- Accordingly in Russia, Poland and Hungary, GDP/capita is higher than what the trend line in institutional pillar suggests; Turkey’s data point is just on the trend line.

Results:

- Turkey’s ranking in most of sub-sets of institutional quality improved over the past ten years; but recently we are seeing some deterioration in multiple aspects institutional pillar.

- Within WEF’s GCI 2014 data, Turkey falls back in institutional pillar even though its headline ranking does not change. Deterioration in judicial independence, public trust in politicians and reliability of police services is holding back Turkey’s performance.

- Additionally, even though there has been no deterioration within the past one-year, business costs of terrorism as well as crime and violence, have been traditionally eroding Turkey’s competitiveness.

- Data plotting on 15 EM that we look at shows countries, which have higher institutional pillar ranking compared to overall competitiveness ranking, have higher GDP/capita. Turkey is just on the trend line plotted, suggesting the its GDP/capita is within its institutional limits. Further erosion of institutional capabilities (as in 2013-2014 data) would put Turkey in a zone where the correlation between institutional quality and GDP/capita becomes stretched.

- March 2023

- February 2023

- September 2022

- April 2022

- February 2021

- June 2020

- March 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- October 2018

- August 2017

- June 2017

- February 2016

- October 2015

- May 2015

- March 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- September 2014

- April 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- July 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013